I stood among the silent audience in the dim living room. The words I had spoken were fading. I turned, emerging from my long, black vail. “They call up from below, from afar into the distance.” Slowly, I walked to the room where the haunted harpsichord waited. I breathed. I lifted the mallets; I reached inside. And I listened.

I was ten when I stopped to consider what lays inside of those creatures we call Keyboard Instruments. That was when I met a “wizard” with round-rimmed glasses and a little magic bag: Mr. Al. Mr. Al arrived in the wake of a very old Schubert piano.

The Schubert Piano Company was headed by a Mr. Duffy, and it revolutionized the American music scene. (Next time you hear the melodious rattle of a honky-tonk, nod wisely, and say: “Ah, yes! A Schubert!”) Our new Schubert was not of the bar-side sort—rather it was an ebony parlor grand—but you couldn’t tell so from the disgruntled tuners who came and went only to make the piano sound even sorrier. Those tuners were obviously sorry for themselves and for my family’s rebellious estate sale find! All tuners, that was, except for Mr. Al. This Steinway technician sat before our Schubert, played some jazz, smiled, said “this is a good piano,” opened his little magic bag, and proceeded to tune by ear while little me watched in awe.

Mr. Al knew how to make a piano sing! He explained everything about their insides: why there are three strings in the treble, why a piano breathes in and out like we do, how the pedals work, and how to listen with him to the stretching and warping of pitch. Finally, one day, Mr. Al said the piano’s action needed adjustment so my tiny fingers would not have to work as hard. So, to my amazement, he simply took the keyboard off. Before me lay the keys, the hammers, and the toothy things which connect them. Left inside the piano was the empty crevice where they all lived. And, deep within, was the dead moth who lived there too.

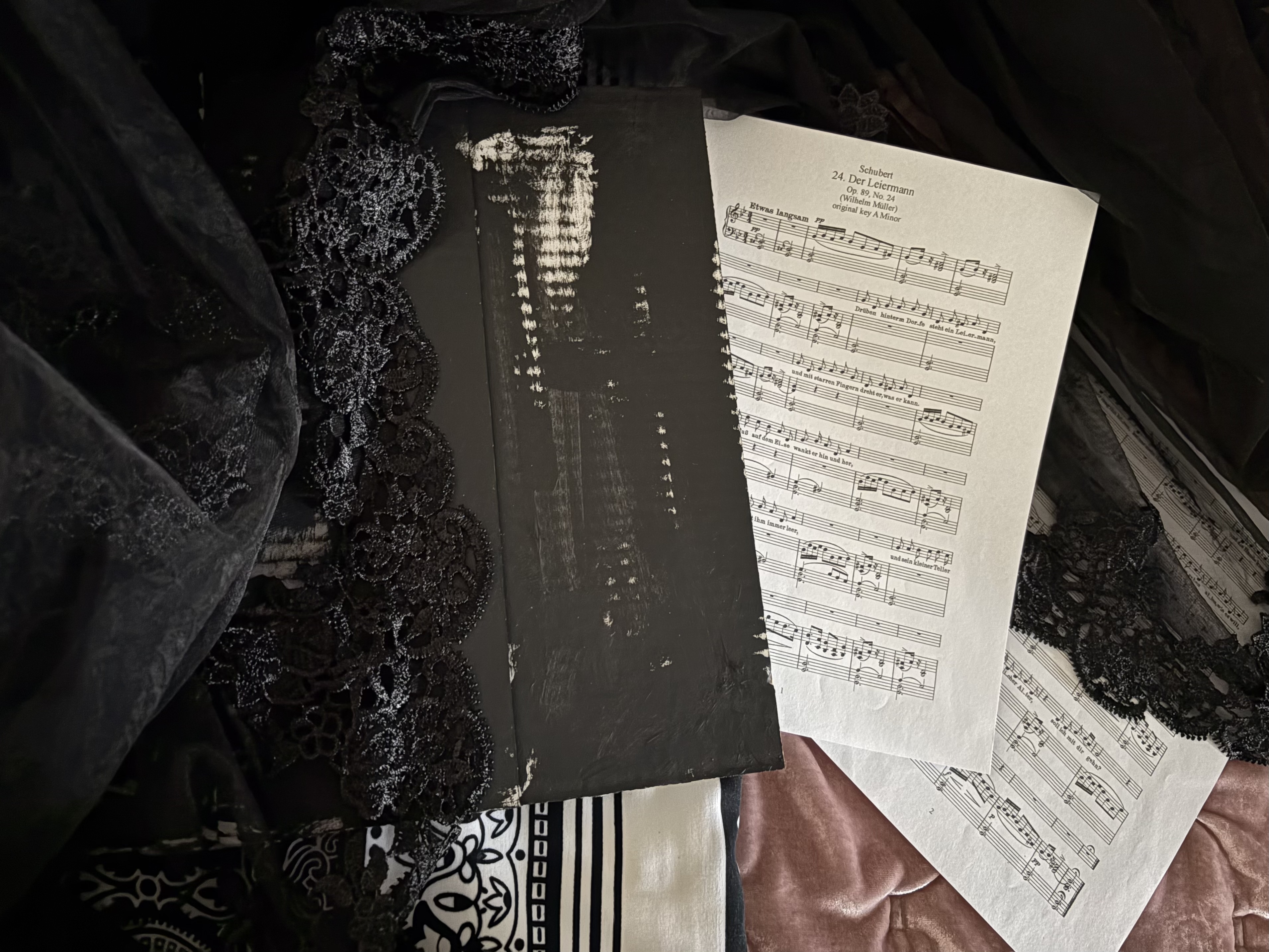

Years later, in late 2025, I was in the home of Dr. Heidi Hart. Ms. Heidi—a masterful arts researcher, curator, and instructor—had invited me to participate in an evening of Hausmusik: an “informal musical tradition from Germany and Austria, where friends still gather to listen, play, and sing with minimal rehearsal,” as Ms. Heidi writes. The musik to be performed was from Franz Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise or The Winter’s Journey. I was to act as ghost narrator: haunting the house in stoic black and reading aloud translated fragments of Elfriede Jelinek’s theatre piece Winterreise, “a meditation on various forms of exile, loss, and melting ice.”

And, during the final song “Der Leiermann,” I was to play Ms. Heidi’s decayed East German harpsichord—from the inside. I remember the fascinating moment when I first met the harpsichord: the keys stuck and unstuck spontaneously with the weather. The strings were brittle yet strong—think of silvery, unbreakable spider’s silk. And, here too, history’s invisible spiders had captured dead moths on the cracking soundboard.

Ms. Heidi showed me how to stroke the harpsichord’s strings with soft mallets and pick them with wood. When I did, the bass tremored and echoed, the edges crackled with disjointed chromaticism, and the higher register gave piercing cries like the whistle of wind in treetops.

Strings of perspectives: that evening of Hausmusik was more experience than performance. The ghost I embodied moved in unexpected ways. The words evolved in meaning as I read them. The sounds came more alive when I stopped to listen.

Winterreise tells the journey of a wanderer with a mangled heart who says good night to his lost love one last time and embarks across a barren winter landscape. He berates his tears for freezing on his cheeks when he is burning inside. He comes by the linden tree which bloomed in his past but does not stop there for peace. He carves his love’s name on a frozen lake like marks on a gravestone. Perused by crows, he enters a sleeping village but, yet again, excepts no rest. At last, as three phantom suns set, he comes across a bare foot old man playing a hurdy-gurdy. And our wanderer is broken to the point of seeing and hearing what no one else does.

“No one wants to listen,

no one looks at him,

and the dogs growl

around the old man.

“And he lets everything go on

as it will;

he plays, and his hurdy-gurdy

never stops.”

Who is this old man? Is he death like many believe? And if so, does death really mean what we believe it does? Isn’t winter a death? Isn’t winter also a re-birth? Don’t we all experience winters? Don’t they force us to pause and change perspective—like seeing a piano from the inside and stroking a harpsichord’s strings? What pains have I suppressed that, in fact, make me stronger? What ever-present wonders have I ignored? Are we holding our hands in front of our eyes or peering with curiosity through our fingers? What are we missing when we don’t stop to listen?

We all will freeze. But will we stay numb? Or will we emerge and bloom?

I hope we choose to bloom.

“Those who come after, who can know nothing, move out of the light they spread with their flashlights, out of the cone of light, only into the darkness. And the strangers, the dead, who were torn out of the darkness of their childhood and were allowed to keep nothing, were not allowed to keep anything, not even their teeth, not their glasses, not their hair, not their dental fillings, not their suitcases … nothing, nothing, they preceded us into where we are today … But at the same time, we. We cut into our tree bark of memory.

The words of love.”

— Elfriede Jelinek, Translated and Fragmented by Heidi Hart

Text of “Der Leiermann” by Wilhelm Müller translated by Richard Wigmore.